Raising money. Part 1 - How VC's work

Photo: The Money Changer and His Wife

This is a 5 post series to prepare you to raise venture capital:

- Part 1 (this post) - How VCs work?

- Part 2 - Reaching out to VCs

- Part 3 - Short story about the pitch

- Part 4 - Questions to ask VCs

- Part 5 - 50 shades of VC No

Raising money from venture capital means that you are entering a long-term relationship. By understanding the VC business model, you are prepared for this relationship and have an understanding of decisions and why they are the way they are.

Venture capital

There are various ways how to finance your startup journey and venture capital is one of them. In comparison to other sources of capital like public funding, and a bank loan, venture capital gives you less bureaucracy and you don't have to return the money. The downside is that you and the team are not the only owners of a business anymore. VCs become part of your cap table and thus have a say about the direction of a business.

Venture capital firms raise funds to invest. Firms usually will have several funds - some with an active investment period, some in the exit phase when the firm look for portfolio exit opportunities. Each fund has some sort of investment theses. Sometimes it is very specific - we are co-investing in health tech and hardware businesses. Sometimes it is vague - we are investing in European startups.

The fund is raised from different sources - wealthy individuals who don't want to invest directly, banks, insurance companies, family offices. They are called Limited Partners and referred to as LPs. The motivation for LPs is to diversify their investment portfolio. They will have some real estate, stocks, bonds, and then this small high-risk/high-reward investment in a startup investment fund. Essentially the process is very similar to how startups raise capital. Partners will go out and pitch their team, and investment hypotheses and try to get money for the fund.

Some math

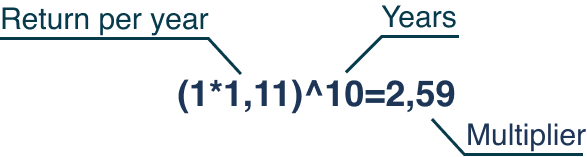

It is important to understand VC math as it is at the core of the business model and directly will affect your business. Let's jump into the VC business.

We are about to launch our VC fund and going to raise 50m to invest in early-stage companies. First, we will have to agree on an investment period - a period after which we will return the money to LPs (hopefully) with upside. It will vary and usually is between 10-15 years. From your startup founder perspective it means that if you have got an investment, VC will look for some kind of exit towards the end of this period. Now we have a timeframe.

Next up is the yearly interest rate or simply put - how much this money cost per year. LPs want to earn money and startups are more on the risky side. This risk has to be balanced by potential return. Return on investment (ROI) is compared between different asset classes - index funds, stocks, bonds, and real estate. Index funds are one of the safest bets and historical return around 5-7% per year. Investment in startups should beat this. So it has to return around 10 - 12% per year. We are talking about year-on-year returns which are cumulative. 10% per year mathematically is 1*1,1. Over 10 years it would be(1*1,1) ^ 10. Now we have a coefficient - 2,59 - a multiplier we can use to understand how much money we have to return.

Practically speaking - a 50m fund multiplied by 2,59 will be the amount we aim to return to our investors after 10 years or 129,5m to be exact. But we also have to earn something as a VC firm. So generally VC industry would round this number to 3x. In our 50m fund that would mean that after 10 years of hard work, we are looking forward to have 150m.

Practically speaking - a 50m fund multiplied by 2,59 will be the amount we aim to return to our investors after 10 years or 129,5m to be exact. But we also have to earn something as a VC firm. So generally VC industry would round this number to 3x. In our 50m fund that would mean that after 10 years of hard work, we are looking forward to have 150m.

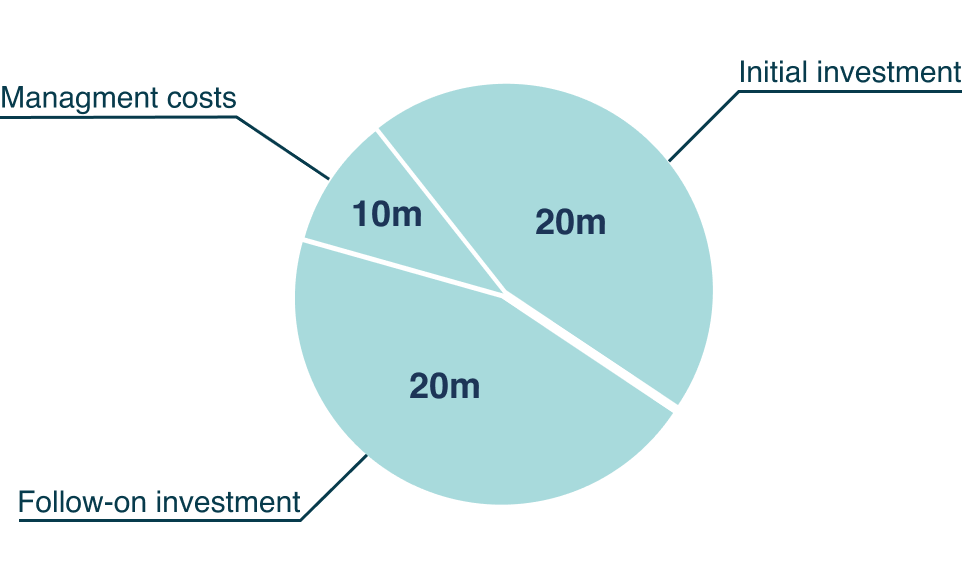

The plan

Math is clear and we have managed to raise money from LPs. Let's build a portfolio. Hold your horses. We have to have a rough financial plan and investment thesis. Usually, VCs will make an initial investment and then have the capital to invest in follow-on rounds to keep their share. In other words, make an initial investment and double down on winners. In our fund we will allocate 20m to actual investments, 20m for follow-on investments, and 10m for salaries and expenses. I know, 10m for the management team is a lot. But for sake of simpler math, let's stick with this.

Building portfolio.

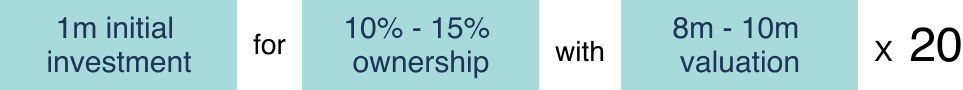

Now we can build a portfolio. Our strategy will be more on the safe side. We will invest in late seed, Series-A deals around 1m per deal and acquire around 15% ownership.

Long story short, in 5 years we have to make 20 investments of 1m and get a share of a business between 10-15%. Sometimes investing more, sometimes less. Sometimes getting a bigger share, sometimes smaller.

After 5 years we start to look for exit opportunities and return the fund. In the process, we might be raising the next fund.

After 5 years we start to look for exit opportunities and return the fund. In the process, we might be raising the next fund.

Some more math

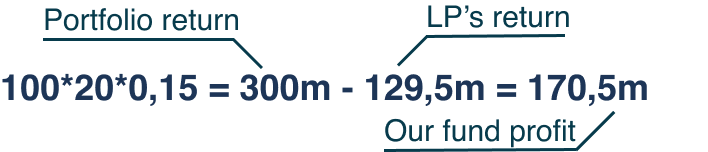

Let's go back to the math here. We have to return that 129,5m and so we can calculate how much we have to get from a single company. We have a portfolio of 20 companies and we have got a 15% stake in each of them.

If a company has an exit of 100m or more, our share will be around 15m. 20* 15m = 300m. Nice. Not only we have returned the fund but also earned 170m for ourselves.

Exceptional job - champagne is poppin' and we are industry stars. The problem here is that a lot of startups die and survivors have to raise a lot of capital.

Exceptional job - champagne is poppin' and we are industry stars. The problem here is that a lot of startups die and survivors have to raise a lot of capital.

If we consider that we are very good investor and 20% of our companies get to an 100m+ exit, then those would be 4 startups from our portfolio.

4* 15m is 60m. We are 69,5m short of our 150m.

4* 15m is 60m. We are 69,5m short of our 150m.

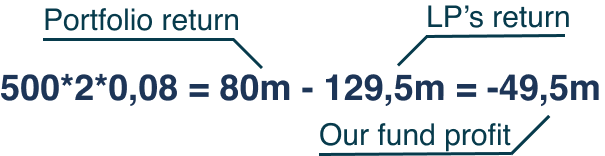

To return the fund we have to have at least 2 companies to have an exit value of 500m+. And these exits aren't that many. It also means that those companies most likely will go through multiple investment rounds and eventually our share will be diluted. Our ownership would be closer to 5%-8% instead of the initial 10%-15%.

With this in mind, let's see where we are.

Not AS bad as before but we are still having -49,5m.

Not AS bad as before but we are still having -49,5m.

Only thing we can aim to change here is company exit value. To return the fund and make a profit, we have to have an exit value above 1b.

Finally, we have got profit of 30,5m. Sounds great. Remember that this comes just from two exits. If one doesn't work out, we are back in -49,5m land.

Finally, we have got profit of 30,5m. Sounds great. Remember that this comes just from two exits. If one doesn't work out, we are back in -49,5m land.

This is hypothetical example with a goal to present portfolio dynamic with different scenarios. You can build simple spreadsheet and play around with these numbers to get a feel.

VC perspective

This is a simple framework that is the basis for VC fund strategy. There are several ways to return the money. Investing small tickets in a lot of very early companies (Pre-seed, Seed), taking a bigger chunk of equity, and betting more on founders, the team, and "they will figure".

Or investing bigger tickets in later stage companies (Series-A, Series-B+), having a smaller amount of equity, and betting more on unit economics, Excel, and "It makes sense".

The strategy also will be affected by the structure of an actual VC firm managing team and their risk tolerance.

In Europe, a lot of funds will have some public funding matching LP capital and thus pressure for high returns will be smaller.

Startup perspective

What are the consequences for you? Because of math, VCs are not looking for good businesses. They are looking for "Go big or go home" businesses - the ones which have big ambition, big market, and skills to make it big.

When you are looking for VC money, you have to be able to show that big bold world-changing opportunity in your story. Not just because it is cool but because the very model of the VC industry requires that. As Jyri Engstrom nicely has put it - Ask yourself, "Do I see myself building 3b company?"

Because of a very small amount of companies that return the whole fund, VCs are willing to see and hear every startup idea. It is pure fear of missing out. It doesn't mean that they actually are going to invest, though.

Your job is to do your research on VCs to understand what is their strategy, approach and if they are fit for your company stage.

At Starwatcher we ask VCs to disclose their fund size and average ticket size. It helps to understand if a particular fund has a strategic fit and saves time for everyone.

Quick note about angels

I have left out angels in this story. Business angels are individuals who will invest their own money. Because of this, their approach is different.

They might invest directly in companies from industries they have some specific knowledge about. To diversify the risk they might create syndicates. In recent years this has become a popular way to invest. Angels also join in later rounds as co-investors.

Getting an experienced angel at the early stage can be a blessing. They tend to be more hands-on and can help avoid crucial mistakes.

Conclusion

Getting venture capital is like getting into a marriage with a termination date. And the number of involved parties will grow after each round. By understanding the intentions and views of each party, you are better prepared to adjust your company course and strategy.

Other perspectives and further materials: